VESSELS & OBJECTS

The beauty of Japanese ceramics extends beyond the iconic tea bowl to encompass a wide range of functional objects such as sake bottles (tokkuri), incense burners (koro), incense containers (kogo), flower vases (hanaire) and food-related utensils such as bowls, plates and kettle lid rests. In the hands of a fine craftsman, these functional pieces, whether they are linked to the tea ceremony or not, are imbued with a uniquely Japanese identity that marks them as works of art. Japan is unique in this regard because unlike many other countries, Japanese culture has never had a clear distinction between fine art, and the highest level of craft. Both are regarded on an equal plane as expressions of the latent potential to produce masterful works of beauty and elegance, using whatever material nature has bestowed. This artistic spirit has flourished for hundreds of years. As the objects in this gallery will testify, this artistic spirit continues to be as vibrant as ever today.

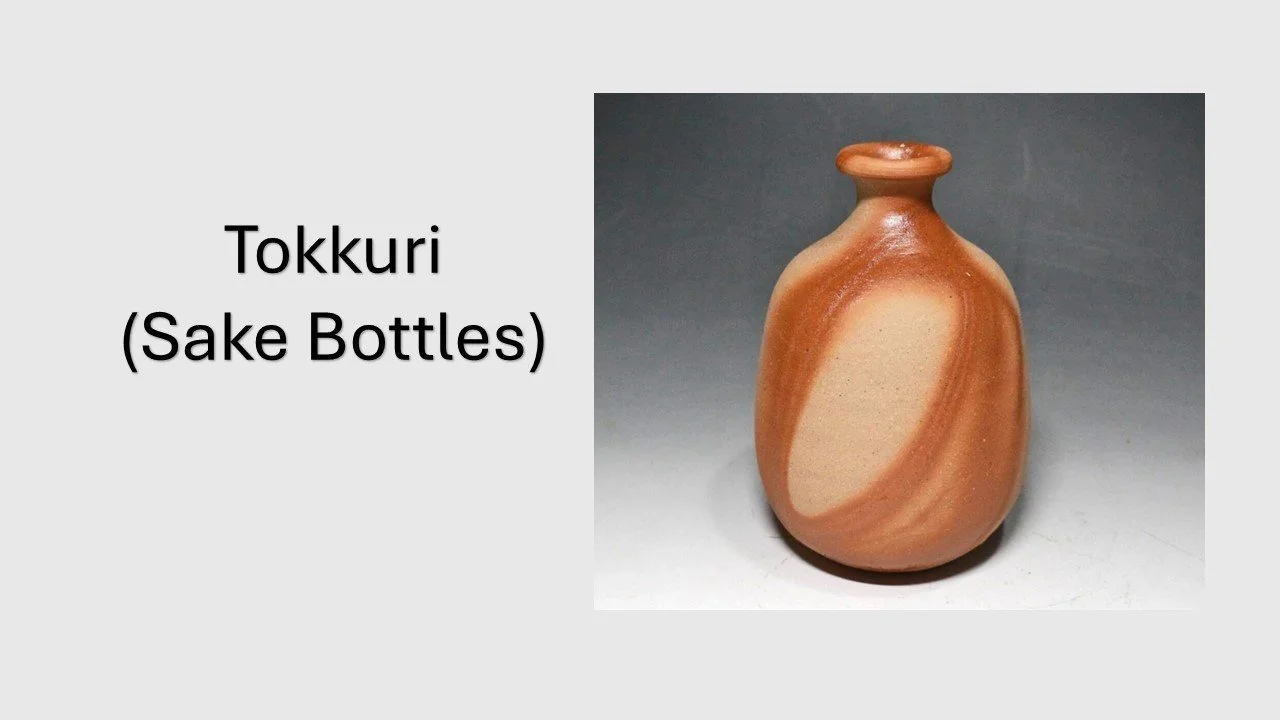

A Bizen tokkuri (sake bottle) naturally embellished with two kiln change patterns on its surface: the goma or sesame seed pattern produced when red pine ash sticks to the ware at high temperature, and tamadare, a glaze-like pattern that is formed when melting ash drips onto the clay body. These and other flame effects accounts for the enduring popularity of Bizen ware, which has a history that dates to the Heian period (794-1185).

This tokkuri features vivid flame marks known as hidasuki which are valued by connoisseurs of Bizen ware. The maker of this bottle, Fujiwara Kazu, comes from an illustrious family that produced two Living National Treasures for Bizen pottery: his grandfather, Fujiwara Kei (1899-1983) and his father, Fujiwara Yu (1932-2000). After studying language and modern history in Europe, Fujiwara Kazu built his first kiln, leveraging on his cosmopolitan background to create modern pieces that are rooted in the centuries-old Bizen tradition.

A petite tokkuri featuring a pinched body covered in hues of gray, black and flaming orange-red, the result of high-temperature firing where colors are formed by the interaction of fire and wood ashes.

Born in 1980, Nakamura Kazuki comes from a family of distinguished potters in Bizen city, Okayama Prefecture. He is the son of the venerated potter, Nakamura Makoto and the grandson of the legendary potter, Nakamura Rokuro.

A flask-shaped vase by the versatile potter, Tasuku Mitsufuji, of a form similar to Korean Buncheong ware that were popular during the late 15th to early 16th centuries and copied by Japanese potters. The vase has a flattened disk shape with a short cylindrical neck and stands on a flared oval foot. It is covered with iron glaze in a dark brown tone, giving it a soft, lustrous sheen.

A porcelain flask-shaped vase decorated with simple abstract calligraphy that alludes to the saffron flower. The maker is the distinguished potter, Takenaka Ko who received of one of Japan’s most prestigious awards (the Japanese Ceramics Society Award) in 1980. In 1995, he was given the title of Intangible Cultural Property of Kyoto for his mastery of porcelain. His works are held in the Victoria & Albert Museum, the British Museum, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo and Kyoto, among others.

A heavy-set Bizen vase with a dark brown surface speckled with sesame seed-like patterns known as goma. The lighter color areas are created by the potter intentionally by shielding these areas from wood ash and flames during firing. The maker of this vase, Isezaki Shin, is the second son of Isezaki Mitsuru (1934-2011), Important Intangible Cultural Property of Okayama, and the nephew of Isezaki Jun (b. 1936), a Living National Treasure of Bizen ware.

A caddy-shaped flower vase by Living National Treasure, Fujiwara Yu featuring the Fujiwara family’s signature opalescent purple hue, enhanced by the skillful drawing out of two prized ash glaze effects: goma (the sesame-seed pattern) and botamochi (round patterns of lighter color that resemble the Japanese botamochi sweet).

Fujiwara Yu was a Japanese ceramic artist known for his work in Bizen ware. The son of Living National Treasure, Fujiwara Kei, he was himself designated a Living National Treasure in 1996 for his efforts in preserving and teaching traditional techniques of Bizen pottery. His work is celebrated for their finely textured surfaces and mastery of firing effects using only wood ash as a glaze.

A rectangular Bizen vase by Isezaki Koichiro featuring striking yohen (kiln-change) patterns created by the interplay of the artist’s skill and the unpredictable effects of high-temperature wood firing. Born into a famous Bizen potter family with two Living National Treasures in Bizen pottery (his father, Isezaki Jun and his grandfather, Isezaki Yozen), Isezaki Koichiro carries the heritage of Bizen to the modern age with innovative forms and an artist’s eye for colors and patterns. A student of American sculptor Jeff Shapiro (b. 1949), Koichiro established his kiln in Bizen, Okayama prefecture after his return to Japan and has since exhibited extensively in Japan and abroad, winning coveted prizes such as Ceramic Art Grand Prize in 2011 awarded by the Paramita Museum in Mie Prefecture and the 2022 Japan Ceramic Society Award in recognition of his outstanding contributions to Bizen pottery. Museums that hold his works include the National Crafts Museum, Kanazawa, the Paramita Museum and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

This dainty vase is meant to hold a single or few flowers. Its surface is covered with vivid streaks of biege, brown, persimmon and black in a style reminiscent of old Mashiko ware. This particular vase was made by artisans working with Tsukamoto Gama, located in a mountain village in Mashiko city, Tochigi Prefecture where the clay was sourced. It was in this area that the Mingei master, Hamada Shoji took Mashiko ware to a whole new level by infusing it with a distinctive folk art ambience. The design of this vase pays homage to that tradition while looking decidedly modern.

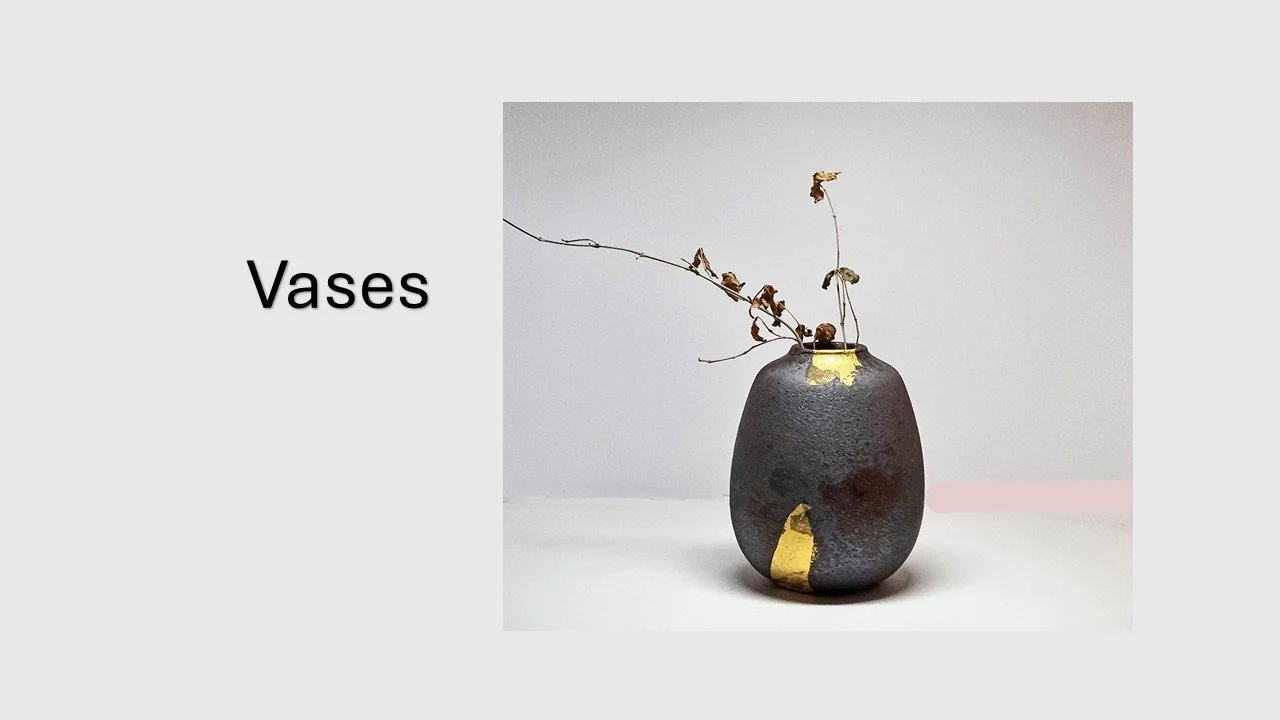

A small vase by Kitamura Takashi decorated with gold leaf on a dark ash-glazed surface. Born in Ishikawa, Kitamura Takashi is known for works that resonate deeply with Japan’s historical and cultural narratives. A distinguished figure in Kutani ware, he has exhibited in the prestigious Nitten Exhibition in Japan as well as internationally.

A rotund vase with a curved foot, meticulously crafted using the coiling technique in which strings of clay are piled up and then hand-molded to the desired shape. The grass patterns on the surface are hand-drawn before biscuit firing and slip application. The artist, Mori Katsushi, is an accomplished ceramist in Japan although he is relatively unknown abroad.

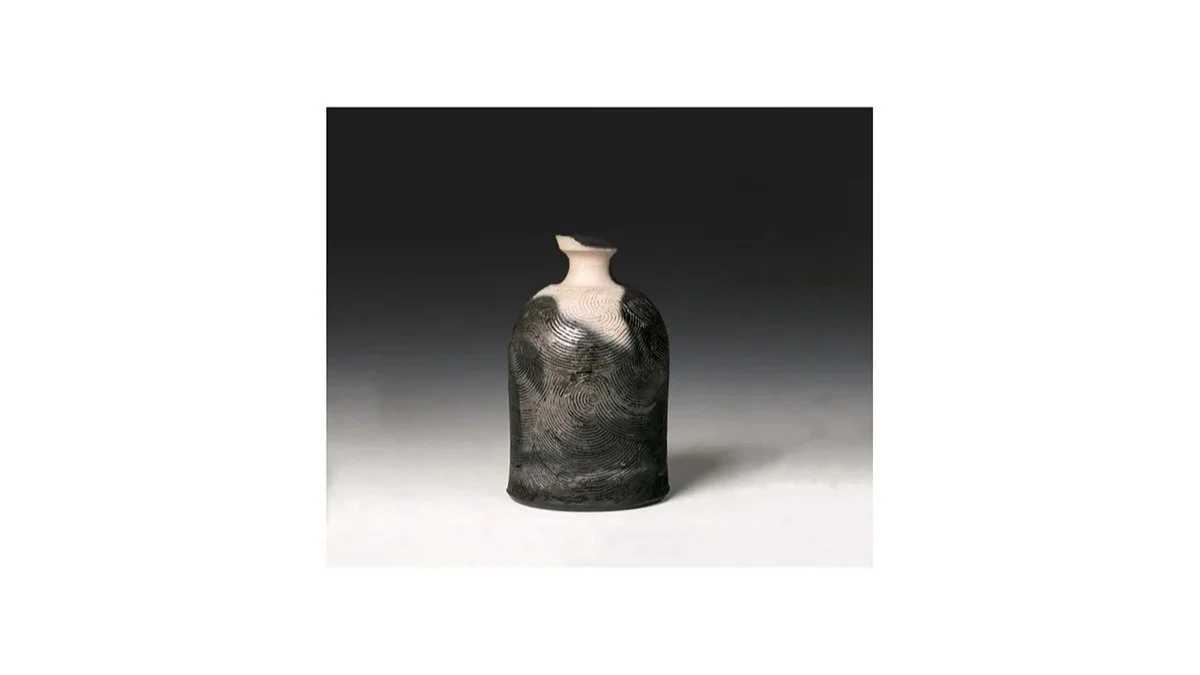

A bottle-shaped charcoal glazed vase with finely incised spiral patterns reminiscent of prehistoric Jomon-era earthenware. Born in 1943, Sakata Jinnai studied under Kamoda Shoji and began his independent career in the Mashiko area of Tochigi Prefecture, where he built his own kiln in 1966. Sakata's work has been exhibited extensively. Institutions that hold his works include the British Museum, The Rockefeller Foundation, Waseda University and Beijing Seika University.

A bottle-shaped vase with a web of fine glaze cracks on the surface, formed during wood firing when iron-rich Shigaraki clay comes into contact with the wood ashes.

A voluptuous cube vase in cornflower blue with four sides curving gently from the base to form a square opening large enough to hold a big bouquet of flowers. On closer inspection, a greenish tinge can be seen near the bottom that reveals subtle brushstrokes of darker hues. The overall construction suggests a twilight scene in the wild (Monet’s famous painting, ‘Blue Water Lilies’ comes to mind).

Born in Kyoto, Fujihira Shin came under the influence of two of Kyoto’s most eminent potters: Kawai Kanjirō and Kiyomizu Rokubei VI. He is known for his delightful, often humorous, ceramic forms and is also a master in creating functional vessels with subtly colored surfaces. His works are held in the National Museum of Modern Art in Kyoto and Tokyo, Musée Tomo, Tokyo, the Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo among others.

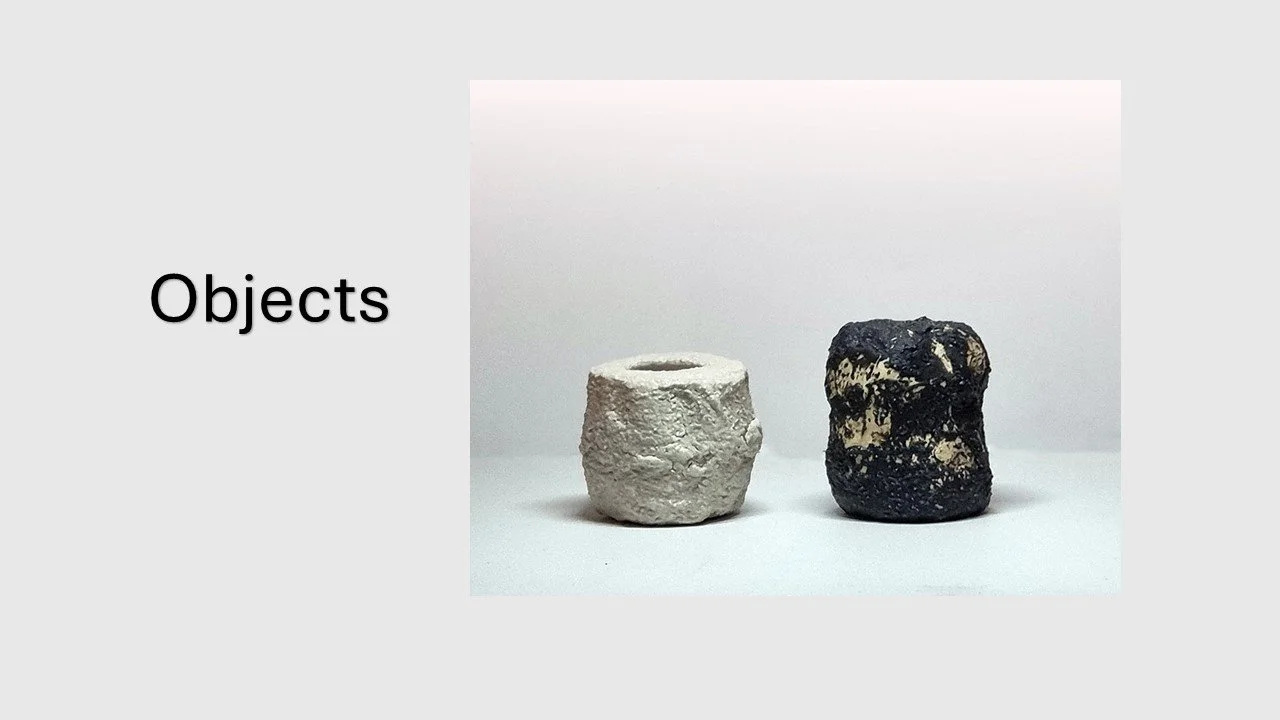

Two small vases by Myoshu Wataru, both unglazed and undecorated to express the essence of wabi-sabi. Born in 1990, Wataru Myoshu is a contemporary ceramic artist based in Kameoka near Kyoto, a place known for artisan heritage. The proximity to the area’s rich traditions in pottery shaped Myoshu’s upbringing, while the beauty of the landscape around his hometown is a constant source of inspiration for his works which uses only soil without any glazes to create vessels with a worn and rustic look that aligns with the wabi-sabi aesthetic.

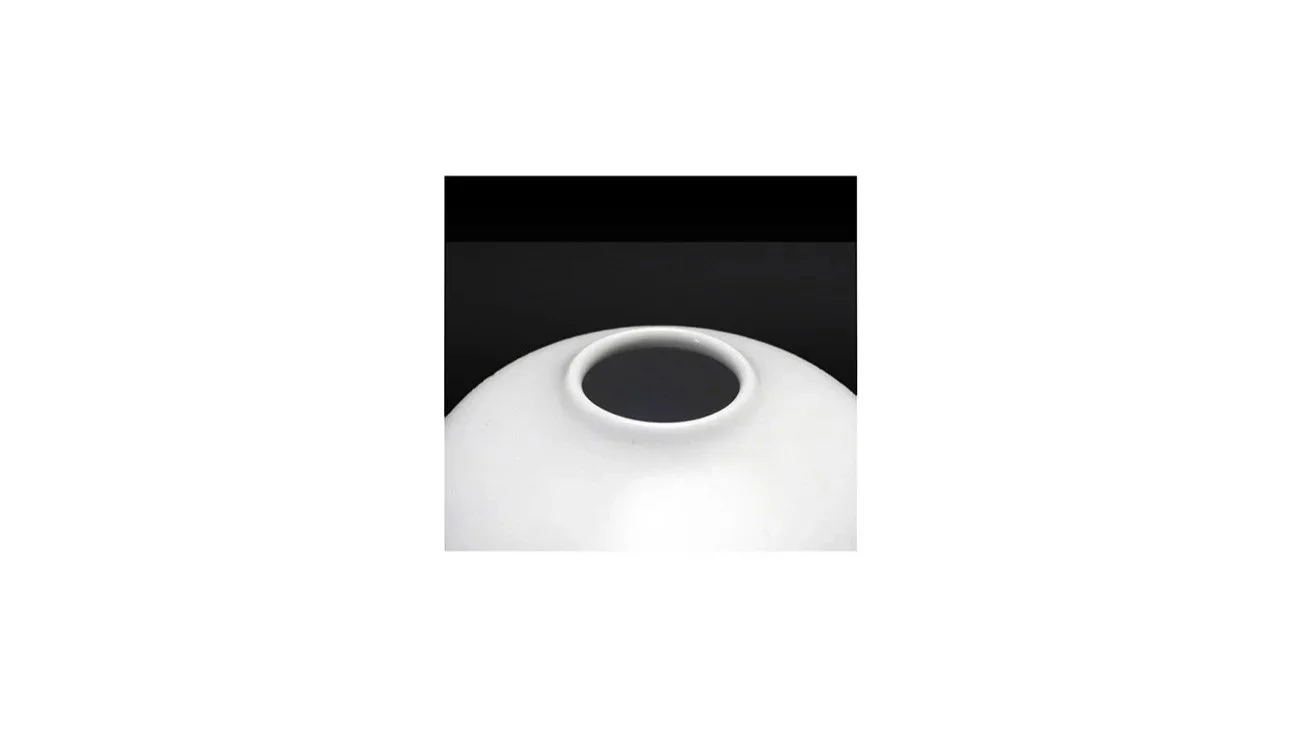

An elegant white porcelain vase by Living National Treasure, Maeta Akihiro who is a master of the curved surface, created using his unique “chamfering technique.” Unlike the conventional method of firing a porcelain vessel after it is formed on a potter’s wheel, Maeta shapes the clay body with his fingers while watching for the timing when it dries. His work is based on minimalism and the purity of white, where the beauty is in the form, silhouette, and subtle shifts of light and shadow rather than added ornamentation. He was given the title of Living National Treasure in 2013 for his mastery of this style which he calls shirashi – the charm of absence.

A minimalist vase by Kazuhiko Sato with abstract decorations of linear designs incised on a rough sandy surface. This is a deeply sculptural piece, conceived as a functional work of art, with a clean and simple appearance that is very much in the spirit of Japanese avant-garde ceramics that bloomed in the mid-20th century.

Kazuhiko Sato is a renowned Japanese ceramicist known for his distinctive modern style. Born in 1947 in Fujisawa (Kanagawa Prefecture), he graduated from the prestigious ceramics department of the Tokyo University of the Arts and studied under Michi Kajimoto and Koichi Tamura, two renowned Japanese potters who are Living National Treasures. He has been presented in major exhibitions around the world and has won multiple awards. His works have also been featured in numerous publications, solidifying his influence and impact on the world of ceramics.

A “frost glaze” sculptural vase by Kato Mami with orange flash decorations on the sides. Based in Tokoname, Japan, Kato Mami has gained recognition for reimagining the classic form of the functional vessel by bringing them into a contemporary realm. She builds her vessels by layering, folding, and draping porcelain clay, then applying a unique matte white glaze on the surface, sometimes followed by ash glaze at the rim. She also employs a traditional Tokoname method of using salt from seashells to create orange flashes as the salt evaporates during firing. Her practice is rooted in an exploration of what constitutes universal beauty. In her own words: “I seek forms that transcend time, silent presences that radiate a sense of universal beauty.” Kato’s achievements have been recognized across Japan. She won first prize at the Shoroku Chawan Competition in 2015, the first woman to win this award in 24 years. She also won the Grand Prize at the Mino Ceramics Exhibitions in 2019 and in 2021.

An exceptional Iga vase by Shingaku Arata who was born in Osaka Prefecture in 1973. After studying pottery under his father, Iga ware artist Shinkanji, he began his ceramic career in earnest in 1999. In 2002, he built a single chamber anagama kiln and held his first solo exhibition, continuing his work to this day. This vase embodies the artist's signature blend of tradition and modernity, utilizing the beauty of Iga ware's distinctive fire color, scorch marks, and vitro (natural glaze) while incorporating a sculptural quality that makes it look uniquely contemporary.

Kogo is the Japanese word for an incense container used in the tea ceremony. They are usually small handheld objects made with clay for the cooler seasons or wood and lacquer for the warmer months. This ceramic kogo has a dome lid and an oval-shaped body reminiscent of a chestnut. It is crafted by a master potter in Tamba city, Hyogo Prefecture. Tamba is one of the six ancient kilns of Japan, known for pottery with warm and earthy tones.

Although small, this incense container exudes a sense of power due its foundation stone-like shape. While the date of its making is unknown, incense containers similar in form to this one have been found dated to the Momoyama period (late 16th to early 17th cneturies).

A hand-carved incense box hollowed out from a block of black clay, and coated with a thick coat of Shino glaze before being fired in a wood kiln for fifteen hours. Born in Germany, Elena Renker migrated to New Zealand where she uses clay from there to make her functional wares that are deeply influenced by traditional Japanese aesthetics.

This incense burner (koro) in pinkish-white tones has a boldly-cut form that is the signature style of Kaneta Masanao, an 8th generation Hagi potter and one of the most influential today. This koro is scooped out from a solid block of clay, instead of shaping on a wheel, which allows the artist to create highly sculptural forms that look like miniature mountains.

Kaneta’s work has garnered much acclaim, earning placement in prestigious public collections such as the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, The Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Japan Foundation in Tokyo, The Museum of Ceramic Art in Gifu, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

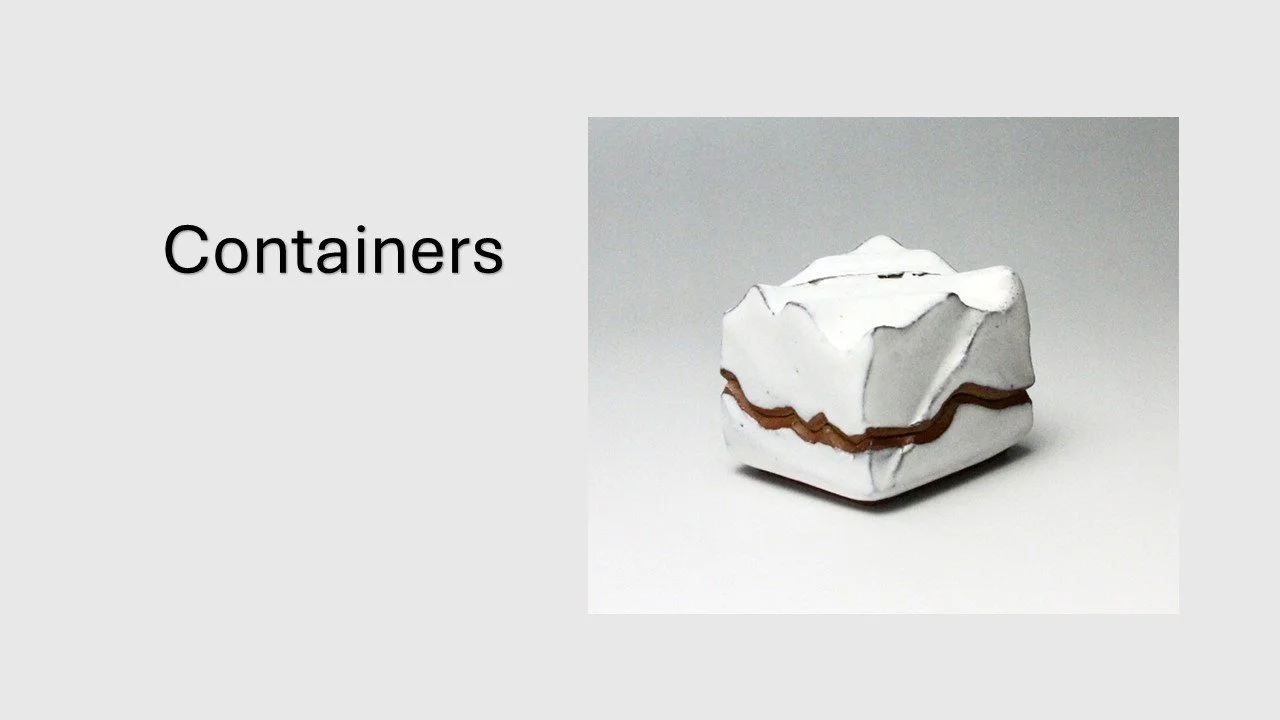

This chamfered kogo is a beautiful example of how functional objects can be standalone works of art. Carved out from a block of clay, the box features an undulating surface resembling a mountain covered with snow. The inside of the container is painted gold.

Born in 1964 in Hagi city, Yamaguchi Prefecture, Funasaki Tohru studied under the renowned Hagi master, Miwa Kyusetsu XII (Miwa Ryosaku). He is a regular participant in ceramic competitions, winning many awards for his modern interpretation of centuries-old Hagi ware.

A contemporary mizusashi (water container) for use during the tea ceremony, modelled after the typical shape of Momoyama-period mizusashis. The body is slightly waisted and the surface is covered with the distinctive rustic texture and greenish-yellow color of Iga ware, a style of pottery traditionally produced in Iga, Mie (former Iga) Prefecture in central Japan. A few spontaneous brush strokes in white and black has been added for artistic flourish. The maker of this jar, Eiji Hayashi, is a second-generation potter of Tsubaki Kiln in the town of Yunotsu, Shimane Prefecture in western Japan.

Chaires (pronounced as cha-ee-reh) are ceramic vessels used to hold high-grade matcha used to make koicha (thick tea). They are some of the most highly regarded tea ceremony utensils. To emphasize this, they are paired with a protective, custom-made silk pouch known as a shifuku, distinguished by their exquisite designs and a precious gold foil on the underside of their ivory lids. This chaire has an elegant and pleasing shape. The body is covered with subtle glaze patterns created by wood ash during firing and the white of the ivory lid provides a beautiful color contrast to the dark brown tone of the body.

A colored porcelain tea caddy (chaire) by Shimada Fumio featuring a simple, clean design of orchids flowers in cobalt blue. Born in Tochigi in 1948, Shimada Fumio studied and taught at the prestigious Tokyo University of Fine Arts. He is a leading Japanese porcelain master whose works follow the footsteps of the great ceramic teachers who taught at the same university, including two Living National Treasures (Fujimoto Yoshimichi and Tamura Koichi). Unlike them, Shimura forged his own artistic identity, creating porcelain works of great elegance and precision using primarily cobalt blue to depict the flowers and plants that he observes on his mountain hikes. His oeuvre ranges from small objects like incense boxes (kogo) and tea caddies (chaire) to larger pieces like jars (tsubo) and vases. His best works have very clean engraved lines reminiscent of early Chinese celadons. In recognition of his artistry, Shimura received won numerous awards and is a full member of the Japan Kogei Association. His works are held by the Imperial Household Agency, the Tokyo University of the Arts Museum, The National Museum of Modern Art Tokyo, the Gifu Museum of Modern Ceramic Art, the Yoshizawa Memorial Art Museum and many others.

A katakuchi (pourer) in a predominant milky white glaze with flecks of black and red Tamba clay peeking through the cracks.

Born in 1948 in Hyogo Prefecture, Nishihata Tadashi is one of Japan’s leading ceramists working with Tamba pottery. He is known for functional and sculptural works that exhibit a refined modern aesthetic while being rooted in a tradition that dates back 800 years. His works are held by the British Museum, London, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Minneapolis Institute of Art in Minnesota.

Shaped like a cup, this katakuchi is a sublime blend of tradition and modernity. Its surface is covered with a lustrous, white glaze, and decorated on both front and back with poetic arc lines that alludes to the shadow of a half-moon.

Born in 1963, Okada Masaru is a ceramic artist based in the small village of Sumiyama nestled in the mountains of Kyoto where the natural surroundings are a source of inspiration for his works. A regular member of the Japan Kogei Association, he has exhibited widely in Japan, winning numerous prestigious awards for his works.

With Bizen ware, less is often more, allowing skilled potters to utilize the natural redness of the clay and the randomness of kiln fire to create vessels of subtle beauty, such as this two-tone cup where beige and reddish-brown hues meet in a way that resembles a Mark Rothko painting.

Born in Okayama city in the heart of Bizen pottery, Takenaka Kenji was trained as a jeweller but switched to pottery late in his life. That turned out to be an excellent decision as he has received high acclaim for his refreshing modern take on centuries-old Bizen pottery.

A refined Chün-glazed cup featuring a satin-smooth grey finish, accented with the potter’s fingerprint marks. Originating from China in the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127), Chün (or Jün) glaze is renowned for its opalescent blue-grey tone. Technically, the glaze is not blue at all. The color in Jun is an optical illusion due to light refracted off from tiny bubbles trapped in the glaze. The glaze itself when examined through transmitted light is actually yellow. The technique of using Jun glaze for pottery became very popular during the Song period and was imitated at numerous kilns across China and later Japan.

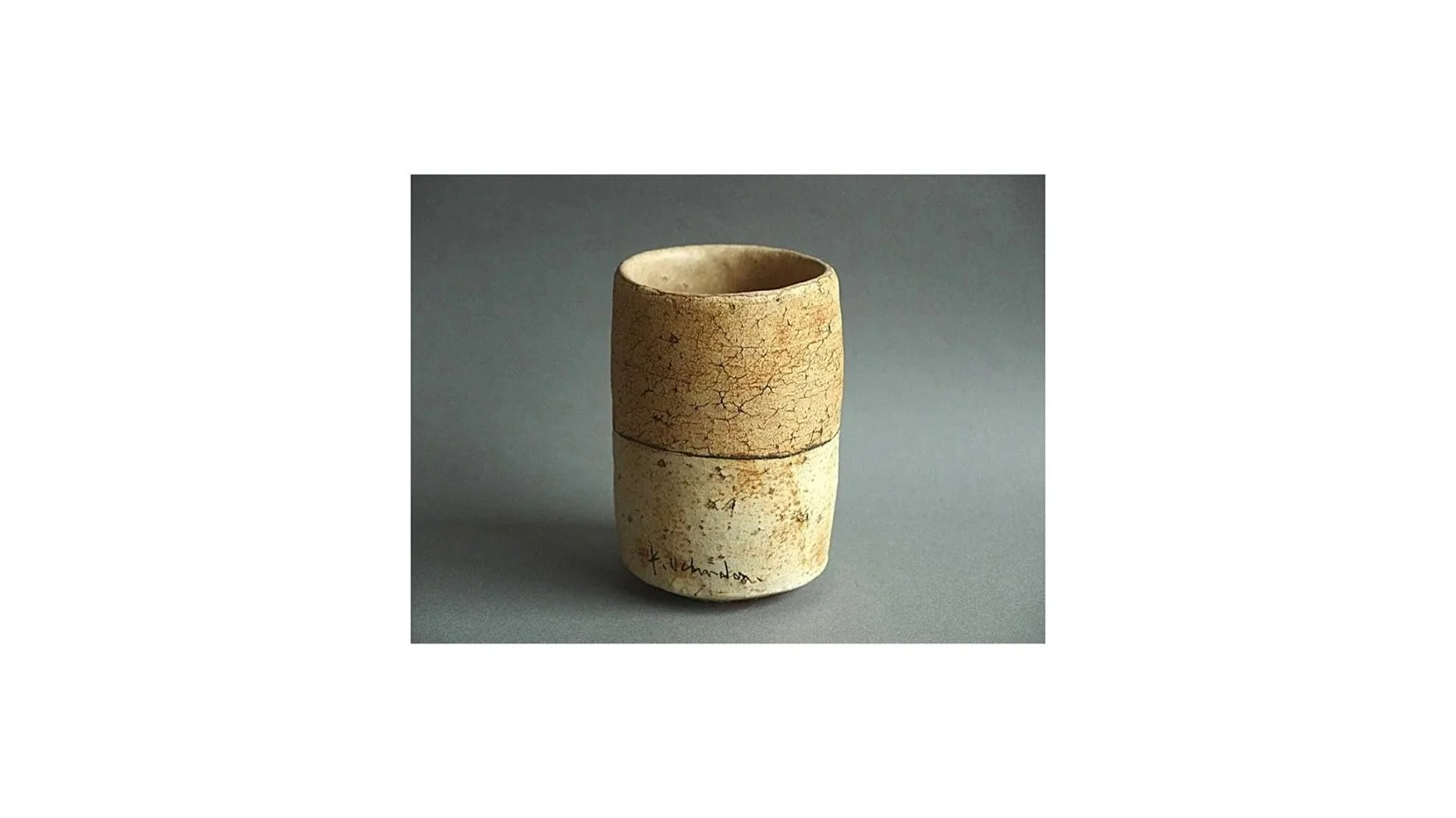

A cylindrical teacup by the painter and ceramic artist, Uchida Koichi featuring elements of the ancient and modern. A distinct horizontal line separates an “aged” top section with crackled yellowish-brown glaze from a lighter, more speckled lower section. With this choice of subtle glaze colors, Uchida succeeds in bringing to ceramics a level of minimalism more commonly associated with Western abstract paintings such as those of Mark Rothko and Agnes Martin.

Born in 1969 in Nagoya City, Uchida graduated from Aichi Prefectural Seta Pottery Senior High School with a Ceramics major. After working as a potter’s wheel grinder in Yokkaichi City, Mia Prefecture, he spent time traveling to many pottery-making regions of the world, an experience which greatly informed his work, which spans many techniques, periods and styles. In 2015, he founded the BANKO Archive Design Museum, a private museum dedicated to the promotion of Banko Ware. Several museums and art institutions in Japan hold Uchida's work in their permanent collections, including The Museum of Ceramic Art, Hyogo, Paramita Museum (Mie Prefecture), and The National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo.

An early e-Karatasu food bowl from the Momoyama period (late 16th to early 17th century). The surface is covered with a light-color crackled glaze and decorated with iron oxide paintings of flora around the rim and two shrimps on the inside (shrimps are symbols of good luck and longevity in Japan). The rough, uneven texture indicates that this bowl was fired in a wood kiln where such imperfections were prized for their rustic quality. Very few Momoyama-period bowls of this quality have survived intact.

A shallow tea bowl by Mitsufuji Tasuku featuring bold brush strokes of white slip on a dark clay base. Bowls of this style were brought from Korea to Japan in the 16th century where they were given the name Hakeme or “brush marks” pottery. The hakeme technique is still prized today for its connection to the wabi-sabi notion of beauty in the rustic and imperfect.

Measuring 24 cm in diameter, this large porcelain bowl by Ito Hidehito has a delicate feel due to its pure white color and thin walls, which makes a bell-like ping when struck gently. The slightly undulating rim and barely perceptible ribbed body adds to the bowl’s graceful appearance as does the restrained use of decoration which is confined to a few spots of glazed flora patterns.

Born in Tajimi, Gifu Prefecture in 1971, Ito Hidehito is celebrated for his contemporary explorations of the porcelain medium. His ceramics are characterized by an elegant delicacy through the thinness of their walls and gentle flowing lines that evoke a quiet sense of movement.

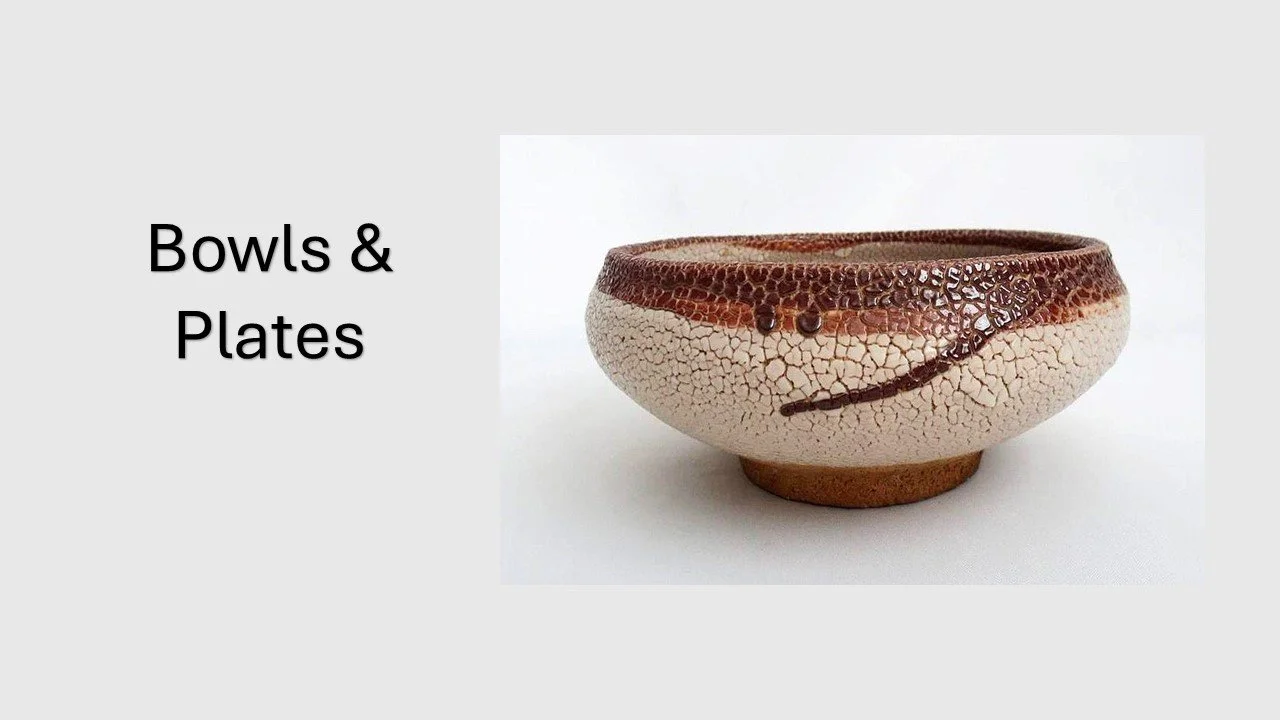

A rare Karatsu bowl featuring a surface pattern known as Samehada-yu or ‘sharkskin texture.’ The texture is created using a glaze that contracts and cracks as it cools, resulting in a distinctive bumpy surface. While the exact origin of the sharkskin glaze is debated, this glazing method was popular during the Meiji period (1868-1912). The dark band around the rim – achieved using iron-oxide paint - is one of the oldest traits of Karatsu ware.

A persimmon dish with iron-painted abstract design by Kimura Morinobu who was born into a pottery family in Kyoto’s Higashiyama pottery district. After apprenticing under his brother, Morikazu, and Living National Treasure Shimizu Uichi, he established his own kiln in 1967. He was selected for his first Japan Traditional Crafts Exhibition at the young age of 26, and thereafter, he has won high praises for his works made using familiar natural materials in ash glazes. His ceramics have been selected for inclusion in major exhibitions and are held in prestigious collections, including the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. In 1990, he was recognized as an intangible cultural property in Kyoto Prefecture, honoring his contributions to the preservation of traditional craft and its impact on Japanese cultural heritage.

A small Shigaraki dish by the versatile ceramist, Kowari Tetsuya whose vessels have a sculptural form that belies their functionality. Shigaraki pottery is celebrated for its rough, rustic appearance due to the natural coarseness of the clay combined with the firing process.

Born in 1970, Kowari Tetsuya studied architecture before switching to ceramics, learning from his father, Kowari Yoshitsugu, who is self-taught. Within three years, he had his first major exhibition of his works with the Osaka branch of Takashimiya and the Shizuoka Prefectural Fine Arts Museum. Since then, he has maintained a steady pipeline of exhibitions at various venues in Japan.

Abstract scratch marks of flowers and leaves hover over the surface of this rectangular plate from Okayama, the renowned center of Bizen pottery. The color tones of tan, dark green and brown are entirely the result of the firing process (the Yakishime method) which relies on flying wood ashes during firing as the glaze.

The beauty of Japanese ceramics lies in their harmony of imperfection (sabi) where clay, fire and time creates vessels that breathe with quiet dignity, like this kettle lid rest by Yuko Ikeda whose works are inspired by nature, particularly the rocky landscape of the coastline she frequents.

A white kettle lid rest by Yuka Ikeda similar in form to the previous piece, deliberately left unglazed to mimic the texture of a rock. Based in Osaka, Yuka’s work is inspired by nature, particularly the rocky landscape of the coastline she frequents.

This is not a vase although it looks like one (there is no opening for flowers), but with this creation, ceramic artist Yuka Hayashi has borrowed an ancient form and given it a modern look using her signature grey Shino glaze. There are also pockets of pink peeking from the surface, a result of iron in the clay interacting with the glaze during firing. A native of Toki city in Gifu Prefecture, Yuka Hayashi has won numerous awards for her distinctive grey and pink Shino vessels. Her works are held in the Mino Ceramic Art Museum and the Museum of Modern Ceramic Art in Tajimi, Gifu Prefecture.

Larger than a sake cup but smaller than a typical vase, this dynamic vessel seems content to be just that: a little work of art. The piece displays the full splendor of Iga earthly textures combined with a captivating blaze of glass-like Oribe glazes, all natural by-products of high-temperature wood firing.

Kazuhiro Fukushima was born in 1981 in Mie Prefecture, the son of the well-known Iga potter, Fukushima Kiyofumi and grandson of the Iga master, Sakamoto Rozan. In 2004, he graduated from the Kyoto Prefectural Ceramics Institute, and the next year, he went on to apprentice with the renowned avant-garde potter, Ryoji Koie. Kazuhiro’s kiln is based near Iga where he continues the tradition of making both functional and sculptural ware with an exceptional eye for beauty.