TEA BOWLS

Japan famously invented the tea ceremony and chado (the Way of Tea), a meditative ritual rooted in Zen philosophy and with it, elevated the humble tea bowl or chawan into an iconic ceramic form. In this gallery, you will encounter traditional and traditional-style modern tea bowls, some dating to the the early years of the tea ceremony in the late 16th to 17th centuries while others are recent makes. All are imbued with qualities that reflect the Japanese aesthetic concept called wabi-sabi, roughly translated as finding beauty in the modest, the imperfect and the impermanent. Since the time of tea master Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591), wabi-sabi has permeated beyond the tea ceremony to many other aspects of Japanese art and culture, including painting, calligraphy, bamboo and lacquer ware. That it has endured when many other art styles have come and gone is a testimony to its profound message, always striking a chord in the spirit of man, affirming our insignificance in a world of constant flux. The tea bowls showcased in this gallery are sublime expressions of this enduring philosophy.

A 17th century black tea bowl by the 4th head of the famous Raku family in Kyoto, Raku Ichinyu who inherited the title of Raku master, Kichizaemon IV, at the age of 16 after the death of his father, Donyu at 58. Ichinyu’s works varied over time, moving stylistically closer to that of Raku founder, Tanaka Chojiro in his later years. This tea bowl, most likely made by a younger Ichinyu, shows several distinct characteristics that identify it as his handiwork: the solid build, low foot, thin walls, and extensive surface spatula marks.

Towards the latter part of his life, Ichinyu invented a thick black glaze mottled with red which had a lasting influence on successive generations of Raku potters (see example in the last image). He is also credited with beginning the practice of signing and writing notes on the tea box.

A Momoyama period Karatsu tea bowl with crackled glaze and gold repairs showing pine, bamboo and plum designs. Karatsu tea bowls have a history spanning over 400 years, beginning in the late 16th century when potters from Korea were brought to Japan to establish kilns in the Hata Clan's domain in Karatsu. Initially serving as everyday ware, they became popular for the tea ceremony in the Edo period, valued for their rustic charm and earthy tones. The careful lacquer repair works on this tea bowl is an indication that it was highly cherished and kept as a heirloom over generations.

A tea bowl by the modern pottery master Yanashita Hideki modeled after the 16th century original by Tanaka Chojiro (1516-1589), the first member of the famed Raku family. Like the original, this bowl is slightly waisted and has an uneven rim in accord with the wabi-sabi notion of embracing the beauty of imperfection. The surface is covered with a matte black glaze with variegated tones of browns and greys resembling rusted metal.

Originally a tile-maker, Chōjirō is especially remembered for his collaboration with Sen no Rikyū, the great master of the tea ceremony who commissioned him to create tea bowls for use in the chanoyu (Japanese tea ceremony).

A tea bowl by modern Raku master Sasaki Kyoshitsu modeled after a 16th century tea bowl by "Renaissance Man” Ho’nami Koetsu (1558-1637) who was a calligrapher, craftsman, lacquerer, potter, landscape gardener, and connoisseur of the tea ceremony.

Named Shirichi (seven miles) for reasons not entirely clear, Koetsu made this tea bowl in a moment of inspiration, perhaps from nature. A striking feature of the bowl is the nearly vertical sides which drop down from the rim like a cliff. Adding to the naturalistic “landscape” are the patches of raw clay peeking out of the black surface.

The maker of this copy, Sasaki Kyoshitu, is a third-generation master Raku potter from Shoraku Kiln, founded in 1905 by Kichinosuke Sasaki, a nishiki-e painter near Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto.

An early Oribe tea bowl of excellent craftsmanship, the surface decorated with lively depictions of geometric and nature motifs probably borrowed from similar motifs found on textiles of the Momoyama period.

Oribe ware was introduced at the end of the 16th century and the beginning of the 17th century. Their debut brought an aesthetic style that was quite distinct from the subdued style of Raku and Shino tea wares. The finest Oribe tea ceramics, including this piece, were produced at the Motoyashiki kiln, which was of the noborigama (multi-chamber climbing kiln) type that permitted a natural updraft from the fire box, and more efficient, even firing. The irregular clog shape of this tea bowl is another distinctive feature of Oribe chawans.

A contemporary Oriibe tea bowl modeled after a Momoyama period original. Like the preceding example, this modern version is clog-shaped and is painted with lively decorations of geometric designs alluding to nature. The maker of this Oribe chawan, Hiroshige Kato (b. 1959) is the 12th head of Kasen Kiln in the Akazu hills of Seto, one of the six ancient kilns in Japan.

A plump aka (red) tea bowl by the respected Kyoto potter, Higuchi Minto, modeled after the 16th century original by Hon’ami Koetsu. Like the original, this tea bowl has thin walls, an uneven rim and a slightly glossy finish due to layers of translucent glaze applied to the surface. Hon’ami Koetsu was a noted designer-connoisseur who played a prominent role in Kyoto’s artistic circles during the late 16th and early 17th centuries. His abilities extended to the making of Raku tea bowls which he learnt from Raku Donyu (1599-1656), the third-generation head of the Raku family.

This shallow bowl is covered with a white slip except a narrow wedge which is intentionally left exposed as an artistic touch. This style originated in Korea during the 15th century and its simplicity won the hearts of many tea masters in Japan. The maker of this tea bowl, Nakamura Yohei, graduated from the Kyoto Prefectural Ceramists’ Technical Institute in 1965 and studied under pottery master Josui Katō.

A shallow tea bowl by Saka Koraizaemon XI (1912-81) who was the 11th generation head of one of the most respected pottery families in the region with a lineage that goes back to the 16th century when the founder, Saka Koraizaemon was brought in from Korea to Japan by the warlord Mori Terumoto (1539-1600). This tea bowl exhibit the fine qualities of Hagi ware such as the smooth crackled glaze in mellow shades of white, beige and orange known as Biwa-iro.

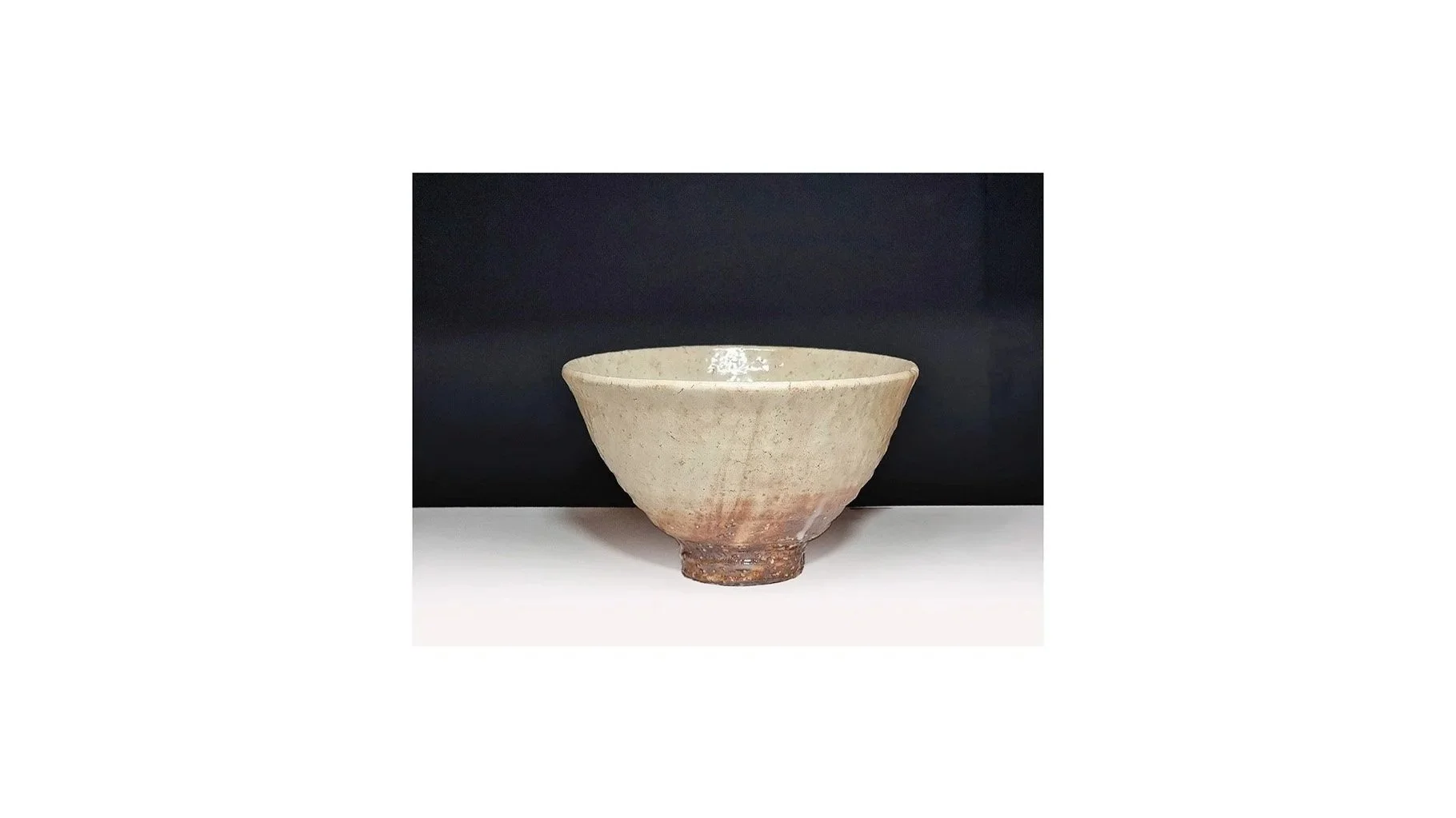

A Hagi tea bowl similar in form to early Korean Ido rice bowls that became highly prized in Japan in the 16th century for their rustic simplicity. The surface of this bowl is covered by a cream colored crackled glaze with the lower part accented with splashes of pinkish red and brown glaze, giving it a modern look.

Hagi clay is commonly used for Ido tea bowls due to its soft, porous and somewhat coarse texture which aligns with the wabi-sabi aesthetic. The maker of this bowl, Matsuno Sohei is the son of the famous Hagi potter, Matsuno Ryuji who passed away in 2005. He now runs his father’s kiln, making contemporary wares that remain rooted in tradition.

A well-balanced tea bowl with natural wood ash glaze by Living National Treasure, Kaneshige Toyo (1896-1967) who specialized in the Bizen style of ceramics. The surface features a rich earthly tone and the celebrated goma (sesame seed) pattern created by the interaction of flame and ash during wood firing. Bizen in Okayama Prefecture is one of six ancient kilns in Japan and Bizen wares have long been admired by prominent tea masters such as Sen no Rikyu (1522-1591) for their unpretentious beauty that resonates with the ideals of the tea ceremony.

A hand-built Bizen tea bowl made using the Shizen-nerikomi technique which relies on the natural color variations of a single source of clay rather than mixing different colored clays (the nerikomi technique). After marbling the clay from one source, it is straw-wrapped and wood-fired for 10 to 14 days with a gradual increase in temperature to a peak of around 1200-1300°C. The present example has a pleasing sand-colored body and striking scarlet flame marks known as hidasuki. Born in Yokohama city in 1948, Kawabata Fumio is a renowned figure in Bizen pottery with a long list of awards.

A plump tea bowl with a deep well and a warm clay body made from coarse Shigaraki clay. The shape is adapted from early Korean Ido bowls whose unassuming appearance endeared many Japanese tea masters. Over the centuries, bowls like these were made in Hagi and Shigaraki, one of Japan’s six ancient kilns. The lineage of such tea bowls dates back to Chinese ceramics from the Northern Song Dynasty in the 11th century (see last image).

A hira chawan is a shallow, wide, and flat type of tea bowl. Its wide, open shape allows the tea to cool down faster, making it suitable for the warm summer months. This example is eye-catching for its black and beige glaze which gives the bowl a modern appearance. One side of the surface is decorated with multiple stamps, a practice that goes back to Raku Chonyu VII (1714-1770). The maker of this tea bowl, Ito Keiraku, is a member of Kyoto’s Katsura Gama kiln founded in 1953.

A masterpiece Setoguro tea bowl by the eminent Mino ceramic artist, Nakashima Masao, with a form that has hardly changed since early beginnings of the tea ceremony in the late 16th century. The bowl features a cylindrical body with a broad squarish base and a low foot. The body tapers slightly in the middle, then rises to a softly undulating everted lip. The jet-black surface provides the backdrop of a dignified scene that evokes a mountain partially shrouded in mist.

Nakashima Masao’s work was first selected at the prestigious Nitten Exhibition in 1956. In 1957, his work was chosen for the annual Asahi Modern Ceramics Exhibition and the year after, he won an award at the same exhibition. His work was purchased by the Emperor of Japan twice and in 1987 he was designated as an Intangible Cultural Treasure of Gifu Prefecture for his mastery of Mino ware.

A rare e-Shino side dish for the tea ceremony meal (kaiseki) made during the Momoyama period (1533-1615). The cup-like dish features a bridge design with scattered foliage around it. The arched bridge is drawn with two parallel lines; its pillars are indicated by four vertical strokes and the guard rails by short lines around the center of the bridge. The brownish color of the surface is due to the thin layers of Shino glaze applied before firing. Shino tea bowls with a very design are held in the collections of the Tokyo National Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

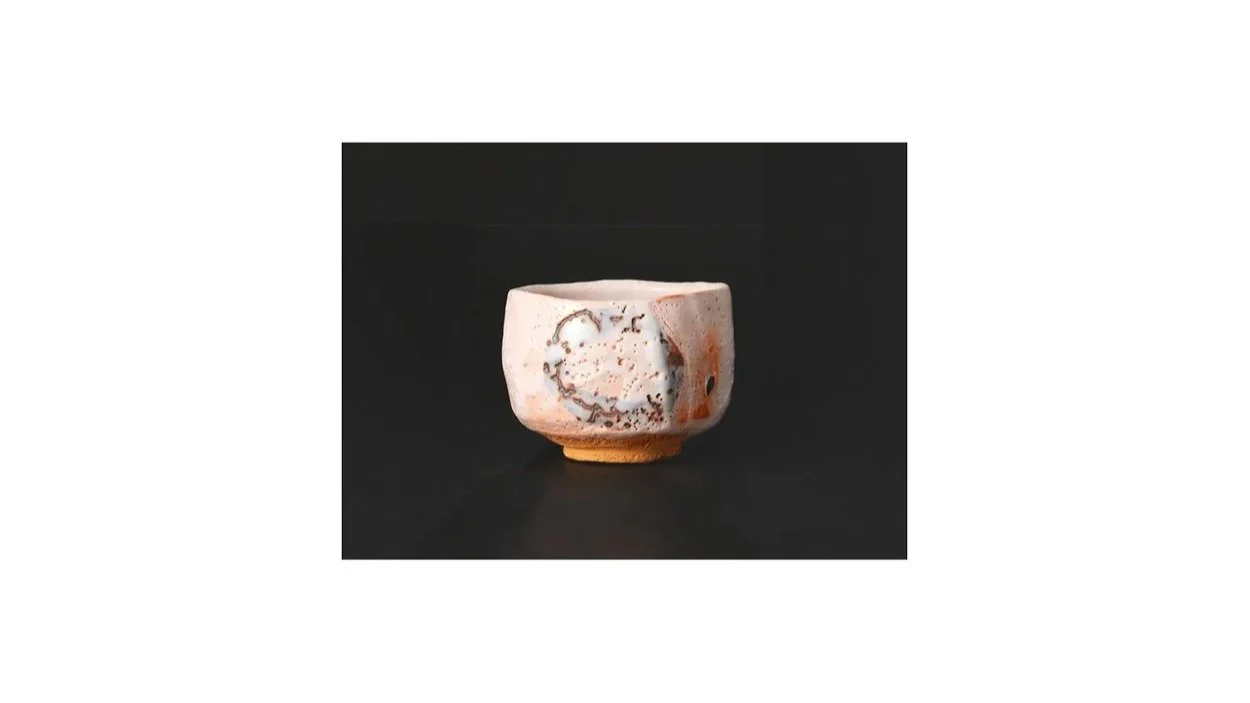

An exceptional Shino tea bowl by Kato Kozo, a revered Mino ware artist and Living National Treasure. The bowl has a gentle curved form and softly undulating rim that speaks to the wabi-sabi sense of beauty. On the pin-hole textured surface, the eye is drawn to a “crawling” Enso circle signifying enlightenment. Blushes of orange “fire colors” and black scorch marks from the wood firing complete the look.

Kato Kozo is one of four Japanese potters given the title Living National Treasure for their contributions to Shino ware. He is a potter in the purest sense. Following his master, Living National Treasure, Arakawa Toyozo (1894-1995) who revived the ancient techniques of Shino pottery, Kato did many things the old way such using a stick-turned wheel and a Momoyama style “cave” kiln as well as the way he carries himself – humble, since, natural and confident. His character is reflected in his works, which are composed and dignified, as exemplified by this tea bowl. The near perfection of this tea bowl is representative of Kato’s oeuvre; he fires four times a year, loading about 220 chawan, but is usually satisfied with only about ten that comes out of the kiln.

In a career that spanned over 40 years, Kato Kozo has received many accolades, including being named Gifu Prefecture Intangible Cultural Property for Shino and Black Seto in 1995 and designated as a Living National Treasure for Black Seto in 2010. His works are highly acclaimed both in Japan and abroad. Museums that hold his works include the National Museum of Modern Art (Kyoto and Tokyo), the Museum of Fine Arts, Gifu, the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, the American Museum of Ceramic Art, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

A modern e-Shino tea bowl in the style of Arazawa Toyozo (1894–1985), a Living National Treasure known for reviving Shino ware after centuries of decline. This bowl shows the distinctive milky white glaze that adorns Shino ware. The surface is painted with a landscape that suggests mist hanging over pine trees and mountains. The irregular shape of the bowl and the potter’s finger marks add to the rustic appearance of the work.

Hasegawa Yoshiaki (the maker) was a famous potter from Toki City in Gifu Prefecture, the heart of the Mino region renowned for its diverse range of ceramic styles that include Shino, Oribe, Kizeto, and Setoguro.

A well-shaped Shino tea bowl with flashes of orange and scarlet on a pitted surface, iron painted with a scene of leaves or grass being blown by the wind. The fine quality of this tea bowl is characteristic of the work of Hayashi Kotaro who was born in Toki, Gifu Prefecture. Hayashi apprenticed with Mino Living National Treasure, Kato Kozo, and quickly mastered the art of Shino ware, producing in his short life time some of the finest Mino pottery ever seen in Japan’s history. He died in 1981 at the age of 41.

An woodfired Shino chawan by Kawai Takeichi who was the nephew of the Mingei master potter, Kawai Kanjirō. At the age of 18, he began apprenticing under his legendary uncle but unlike his uncle’s wildly expressive forms, Kawai Takéichi’s followed a more reserved style. This tea bowl exemplifies his restrained approach, relying only on the slightly distorted shape, and the color and texture that emerge from the wood-firing to express a dignified sense of beauty.

An elegant chawan by the renowned ceramic artist, Kamei Masaru who works in the Seto style. This tea bowl has a pleasing shape and is simply decorated with a few feldspar splashes of what appears to be leaves of grass on a slightly metallic grey background. Kamei Masaru is known for his avant-garde style of pottery often featuring unique glazes. His significant career achievements include winning the Blue-ribbon award, the highest prize at the prestigious Japan Fine Arts Exhibition (Nitten) twice.

A graceful tea bowl by Yamada Kenichi featuring a crackled glazed surface and iron oxide paintings of leaves and flowers. Yamada received many domestic and international awards earning him high acclaim, including the Chunichi Award at the Nitten Exhibition and the Grand Prize of Honor at the third Vallauris International Ceramic Exhibition in France in 1972. He was designated a Cultural Important Property by Tokoname City. His son is the famous contemporary ceramist, Yamada Kazu.

Ki Seto (Yellow Seto) is high-fired ware that originated in the late 16th century as part of the Mino family of ceramic styles. They are characterized by a matte yellow glaze, often embellished with fine streaky patterns known as “hare’s fur,” the result of carefully formulated glazing, high firing temperatures and a specific cooling process. This bowl is a flawless example of Ki-Seto ware with the hare’s fur pattern. Like wind-blown leaves, the “furs” float across the yellow surface , giving the bowl a calming yet dynamic feel.

Nakagima Masao (b. 1921) is a prominent ceramist from Gifu Prefecture. He exhibited at the prestigious Nitten Exhibition as early as 1956. Thirty years later, he was designated as an Intangible Cultural Treasure of Toki City, Gifu Prefecture.

A round-shaped red tea bowl by Higuchi Minto featuring a pair of cranes. Cranes are symbols of good fortune and longevity In Japanese culture, and have appeared in many art forms throughout history. This tea bowl has been been repaired Kintsugi-style using urushi lacquer dusted with powdered copper. Higuchi Minto was born in Nagasaki in 1928 but worked in Kyoto for most of his life.

A refined Gohon (pink on biege) tea bowl by the distinguished Kyoto potter, Kiyomizu Rokubei IV. A flock of fifteen flying cranes are depicted with great attention to details with regard to expression and gestures. In Japanese culture, the number 15 symbolizes imperfection and the beauty of transience as seen in the Ryoanji Zen garden where 15 rocks are present but only 14 are visible at any one time, signifying human limitations.

Kiyomizu Rokubei IV was one of the most influential heads of the Kiyomizu family of potters that has a history of over 240 years. Born in 1848 as the eldest son of Rokubei Kiyomizu III, he inherited his title Rokubei IV in 1883 when he joined the Toyukai artists’ association. For much of his career, Rokubei IV was active in Kyoto art circles, helping to establish various associations to promote ceramic appreciation. He also co-established the Kyoto Ceramic Research Institute in 1895. He retired in 1902 and passed his title to his son, Rokubei V in 1913. His works are often considered the best among the succeeding Rokubei generations. Museums that hold his works include the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Asian Art, The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, and the Cleveland Museum of Art.

A hand-built, multi-textured tea bowl with sides that gently slant to the top. The lower surface is left unglazed while the upper surface is draped in a thick white glaze with subtle touches of blue and black.

Based in Hiroshima, Osada Kouichi opened his kiln in 2023 after apprenticeships with several master potters. His tea bowls are made using glazes from burned rice straw, wood ash, feldspar and rare minerals, and are fired in a thick-walled kerosine kiln that encourages Yohen (kiln change) surface effects.

A hand-built Raku tea bowl with abstract landscape decorations by Maturaku kiln in Kyoto featuring a slightly indented body and an uneven rim. The bowl is covered with a glossy black glaze and accented with lighter splashes to suggest a scenery. Matsuraku kiln has a history tied to the city's ceramic traditions and the tea ceremony. It was established in Kiyomizu-zaka, Kyoto in 1905, and is known for producing exquisite tea bowls for the tea ceremony and collectors of fine tea ware.

A sand color cylindrical tea bowl decorated with drips of white glaze that hints at falling snow. Shoraku Sasaki (b. 1944) is a highly respected contemporary Japanese potter, best known for his deep mastery of the Raku tradition. He is the third-generation head of the Shoraku kiln (estd. 1905), located in Kameoka near Kyoto, an area historically associated with refined ceramics. His work honors the traditional methods of hand-forming and low-temperature firing, yet he brings a distinctive touch to each piece through unique glazes and dynamic forms that bridge classical aesthetics with modern sensibilities, earning him recognition among collectors, tea practitioners, and museums worldwide.

A Raku tea bowl that fuses tradition with modernity through the faceted shape and the use of amber glaze, a color rarely seen in classic tea bowls. The connection with tradition is in the painted landscape which depicts Japan’s most sacred mountain, Mt. Fuji in silhouette at sunset.

Sasaki Yamato (b. 1964) is the fourth generation of the famed Sasaki Shoraku kiln founded in 1905, one of only ten traditional Raku kilns remaining in Japan. The Shoraku title was conferred to the family by Daitokuji Temple with which the kiln has long associations.

A graceful “Moon White” tea bowl by Matsubayashi Hosai XVI who was born in 1980 in Uji, Kyoto to a family with over 400 years of history in pottery making. After learning the potter’s wheel in 2004, he apprenticed under his father and in 2016, assumed the family head title as Hosai XVI. Using clay passed down through generations, Hosai specializes in the making of tea utensils that express beauty and harmony of form and color. One of his most notable creations is Geppaku Moon White tea bowl seen here, where a brush of gold is added to the serene blue and white background that evokes a modern version of Rimpa, a style of Japanese painting popular in the 17th century. Key features of Rimpa, such as the simplified depiction of nature, pastel-like colors in ink wash enhanced by gold paint are broadly seen in this tea bowl, consistent with Hosai’s aim of keeping the aesthetics of traditional tea ware alive while infusing it with a contemporary vision. Hosai’s works have been exhibited in private galleries around the world as well as museums such as the Guimet Museum of Oriental Art in Paris, Kyoto Museum of Crafts and Design and the National Museum of Wales.

Matsui Kosei was designated a Living National Treasure for his mastery of the Neriage (multi-color clay layering) technique, allowing him to create vessels with complex marbled surface patterns, often with a rough-hewn texture. While many of his vessels feature densely packed patterns reminiscent of waves and swirls, for this tea bowl, he gives a lighter touch by blending a few areas of blue to a lightly marbled background, creating a work that is grounded in the traditional wabi-sabi aesthetic and yet refreshingly modern.

A tea bowl by Kazu Yoneda, painted with lotus flowers on a light cream background. Born in Okayama Prefecture, Kazu Yoneda is one of the most accomplished woman artists specializing in porcelain ceramics. Kazu created her signature style of porcelain design completely different from the dazzling colors of traditional Kutani porcelain ware. Her work depicts nature, typically flowers or birds, in sophisticated black and white reminiscent of Chinese ink painting. She is a multiple Japan Crafts Association award winner, and was selected four times for the prestigious Kikuchi Biennale exhibition.